On September 23rd a movie version of Michael Lewis’s bestselling book Moneyball is coming to theaters, starring Brad Pitt as Oakland A’s General Manager Billy Beane. When the book was released in 2003, I bought copies for members of my analytics team, as the story shaped a great deal of my thinking about workforce measurements and to look for metrics that provide insight over the metrics typically on-hand or historically used.

If you’re unfamiliar with Lewis’s book or, like my Russian colleague, not familiar with baseball, let me provide a brief synopsis.

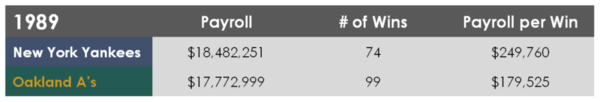

Author and financial journalist Michael Lewis sought to answer the vexing question, “How do small-market baseball teams like the Oakland A’s become competitive in a field of financial juggernauts like the New York Yankees?” In 2006, the Yankees and A’s each won their respective divisions, but while the Yankees spent over $2 million in payroll for each win, the Oakland A’s spent only $669,387 per win.

Source: www.baseball-almanac.com

Lewis’s inquiry boiled down to the question, “How did the A’s become so efficient?”

In short, the answer was necessity. The techniques implemented by the A’s and Billy Beane were not new; they had been kicking around among baseball wonks since the 1970s. What Beane did that was unique was applying theory to practice with fantastic results.

The Oakland A’s were not always a “small-market” team. In the late 1980s, the team boasted stars like Mark McGuire, Jose Conseco, Ricky Henderson, and Dennis Eckersley. At the time, the team was owned by Walter A. Haas, the great-grandnephew of Levi Strauss. While Haas was a shrewd businessman, leading Levi Strauss from its roots as a regional manufacturer to a global apparel brand, he was also a philanthropist at heart, establishing his first foundation with his wife in 1953. As A’s owner, he understood his team as a philanthropic venture for the community and, like all top-market baseball teams, spent lavishly to bring and keep stars in Oakland.

Source: www.baseball-almanac.com

After Haas passed away in 1995, the team was sold to investors with more profit-driven intentions who ran the team accordingly. Payroll was immediately slashed by a third, leaving the team’s management to operate within a dramatically changed landscape (a reality frighteningly familiar to those in corporate American through the last decade) wherein the A’s needed to strategize how they might compete with organizations with comparatively endless resources or other capital advantages.

Source: www.baseball-almanac.com

The answer: By managing talent more effectively.

Talent Management Lesson One: Identify Material Metrics

For decades, big league baseball scouts have looked to five key predictive indicators when evaluating amateur talent: speed, quickness, arm strength, hitting ability, and mental toughness. Some look for “the Good Face,” meaning strong bone structure or the look of a leader. Intuitively, these skills make sense (except, of course, for “the Good Face”), but the methods by which scouts traditionally measured the aforementioned skills were decidedly weak.

For example, to test for speed a scout typically asks prospects to run a sixty-yard dash. Given that the distance between bases is ninety feet, scouts were evaluating prospects on the equivalent of hitting and running a “double”. Why is a sixty-yard dash not an informative measurement? In 2010, the Texas Rangers’ Adrian Beltre, led the MLB in doubles with 49 in 589 at-bats or eight percent of his at-bats. Thus, scouts have been using an at best rarely relevant yardstick to measure speed, one that even in the best-case scenario incorporates greater endurance than what is normally required.

I suspect this seemingly appropriate (in its clear-cut and quantitative) approach is one to which your organization might also fall prey due to the measurement’s ease “for comparative purposes.” Organizations often persist in measuring comparative data that lack meaningful application (such as including questions on employee engagement surveys with which no one agrees) simply to have year-over-year, consistent results.

Recognizing the need for new and additional evaluative tools, the Oakland A’s broke from traditional metrics when recruiting talent from the amateur draft. First, they stopped recruiting high school talent, especially pitchers. This was for three reasons:

- they deemed high school students as years away from being able to play in the major leagues, because

- high school students still have a substantial amount of physical development ahead of them, and

- most importantly, the Oakland A’s believed the market overvalued this talent.

Oakland turned its attention toward recruiting college players in the amateur draft. Not only did college players lack the shortcomings of high school players, but they had accumulated a wealth of evaluative statistics while playing college ball. The Oakland A’s examined stats such as on-base percentage, slugging percentage, number of walks, strikeouts, and if available number of pitches. Through this process, they learned a few truisms:

- The number of walks a player takes is the best indicator of a disciplined hitter.

- Disciplined hitters are born. This is a skill that cannot be taught, at least not at a professional level of play.

- Disciplined hitters can develop power. Power hitters do not develop discipline.

Which measurements, if any, does your organization use to manage talent? Does your organization understand and utilize the key predictors of success in a given role, or are you looking for “the Good Face?” Does your organization know which skills are teachable and which can only be acquired through selecting the right talent? Can your organization quantify potential with data or are determinations only supported by intuition and gut feelings?

Good talent management requires identifying the measurements that are material for organization success.

Talent Management Lesson Two: Identify the Skill Levers that Drive Your Business

For a baseball team, business goals are straightforward: win games (to sell tickets, merchandise, and otherwise generate revenue) and make the play-offs (presumably to sell more tickets, merchandise, and generate more revenue). Traditionally the basic skill levers of baseball are pitching, fielding, and batting. The Oakland A’s were not satisfied with these generic levers. Rather, they started by calculating the value of each play within a game. Using derivative valuation and probability, the A’s were able to dissect players’ skills to understand their true contribution to the team.

When Oakland’s lead-off batter and outfielder, Johnny Damon, signed with the Boston Red Sox, it left two holes for the A’s ― his offensive bat and defensive glove. According to Lewis, “To most of baseball, Johnny Damon, on offense, was an extraordinarily valuable lead-off hitter with a gift for stealing bases.”

If your organization lost a valuable star like Damon, your first inclination might be to find the best lead-off hitter you could afford. The A’s approached the issue differently. They looked at Damon’s on-base percentage and found it was ten percentage points below the league average and, therefore, easily made up elsewhere. They discounted the stolen bases because they calculated that a player had to be successful more than 70% of the time to influence the outcome of the game – a risk the As’ were unwilling to take.

But Damon’s defensive prowess was a great loss to the team and not one they could easily replace. As a result, instead of trying to replace Damon’s defensive skills, the A’s found it easier to add offense that offset the loss. In other words, Oakland expected to give up more runs and made the conscious decision to trade defensive skills for offensive skills.

What is the Talent Management lesson from Johnny Damon?

Organizations need to manage skills more and individuals less. If you don’t see this being done, it’s probably because it’s hard work! Baseball has thousands upon thousands of data points to support a plethora of sophisticated calculations. By comparison, I find that many organizations struggle to agree on numbers as simple as headcount. While we may not be able to replicate the A’s mathematics in our organization, we can strive to apply the technique.

When the next “Johnny Damon” leaves your organization or is promoted, before looking inside and outside the organization for the closest replica, dissect the employee’s true overall contributions to determine their impact on the organization as a whole. Is there a current staff member who can assume one of the key contributions? Which contributions are the most critical or expensive to replace? What is the bottom-line impact of a “lower-quality” contributor, and can any shortfalls be balance out by other strengths?

While it is human nature to want to replace exactly what you’ve lost, it’s often unfeasible, and further it’s not good talent management.

Talent Management Lesson Three: Identify “Value Players” and “Value Roles”

I would like to introduce a new concept to talent management thought leadership. We are long-familiar with the term “critical role,” although its exact meaning can create great debate within organizations. If you have read John Boudreau’s work, you’re familiar with the concept of “pivotal roles.” In the same vein as “critical” and “pivotal” roles, a value role is a position within an organization that the market or the industry has thus far undervalued.

Identifying value roles (or value players) is tricky business because markets are in constant flux. Interestingly, years after Moneyball was published, Billy Beane commented that college players were becoming overpriced and that high school players are now where the bargains lie. In economic terms, the conceptual power of identifying existing value roles is in exploiting asymmetric or imperfect information. The Oakland A’s invested heavily in acquiring better information than their competitors in order to spot the value players.

Moneyball includes numerous examples of value players, such as David Justice (who had merely committed the sin of aging) or Scott Hatteberg (who had ruptured a nerve in his elbow). The Oakland A’s were only able to afford these players because, using Paul DePodesta’s language, “they had known warts.” DePodesta said, “…what gets me really excited about a guy is when he has warts, and everyone knows he has warts, and the warts just don’t matter.” To properly apply DePodesta’s approach requires thorough knowledge of skill levers and of which measurements are material. This inherently logical approach is a fresh paradigm for identifying talent.

In many ways, the Disney Park street sweepers (John Boudreau’s pivotal role exemplar) are also an example of a value role. If you are unfamiliar with the illustration, Disney Parks, the theme park arm of the The Walt Disney Company, evaluated roles to determine if and where additional investment in people would yield the highest impact to the organization’s goal, in this case, to create magical experiences for guests.

Disney found that the difference between the best Mickey Mouse and the worst Mickey did not substantially change the customer experience, but the best street sweepers could delight the customers. While many theme parks might outsource staffing their street sweepers with low-skilled, low-wage workers, Disney Parks found a way to use this resource to enhance the customer experience.

Critical, pivotal, and value roles are not mutually exclusive and can cross categories. The concept of the value role is significant because it’s another mechanism for gaining a competitive advantage. If your organization is able to exploit a talent resource disregarded by your competition, then the result is an immediate benefit.

There are additional talent management lessons to learn from Moneyball including:

- Reconciling your talent needs versus your talent wants

- The superiority of behavior-based interviewing to evaluate candidates

- Building bench strength is a fool’s errand.

But for this article I want to cover one last lesson.

Talent Management Lesson Four: If You Are Doing It Right, the Establishment Isn’t Going to Like It

As one of my mentors Jay Jamrog says, “People, especially leaders, have ‘educated incapacity,’ meaning that they are so invested in how things are done today, they cannot imagine doing it differently.” Talent management is far from immune to this phenomenon – despite management consistently demanding that HR “fix talent management” – our organizations are often not prepared for the changes required.

In later printings of Moneyball, Michael Lewis describes how the book was received and openly “apologizes” to the Oakland A’s and defends Billy Beane. It seems that the baseball establishment perceived the book and Beane as attacking their way of life, their logic, their traditions – and in some ways this is true. Beane became baseball insiders’ public enemy number one, accused of being a braggart, a shameless self-promoter, and an egomaniac, which could very well be true, but according to Lewis, it is inconsistent with how Beane presented himself during Lewis’s research of the Oakland A’s.

Lewis addressed Beane’s critics directly:

“The point is not that Billy Beane is infallible; the point is that he has seized upon a system of thought to make what is an inherently uncertain judgment, the future performance of a baseball player, a little less uncertain. He’s not a fortune teller – he’s a card counter in a casino.”

This is what we can do in HR to create talent management that makes a significant difference within organizations. It’s about being systematic, reducing risks, and placing statistically probable bets. Did you know that successful professional gamblers only win about 55% of the time? Further, at the time of writing, the Detroit Tigers have secured the American League Central Division title with a winning percentage less than 60%. This means that a liberal amount of failure should be expected. We cannot let these expected failures become a justification to stop, start over, or re-engineer the talent management process when it gets uncomfortable for management.

HR organizations of all sizes and types have been wrestling to unlock the value of talent management. The issue is not a simple one; after two years of research and interviewing dozens of professionals and thought leaders, I still have not discovered a meaningful definition of talent management. Behind this frustration may be that as HR professionals we continue to tackle the issue with our current set of tools, rather than looking for a new toolbox. The Oakland A’s story demonstrates there can be great rewards for those who take the risk of looking for a novel solution to old problems.